The remains of Arbourville are located between Maysville and Garfield on the south fork of the Arkansas River, between mile marker 208 and 209 on Highway 50. The former town site is directly south of the highway, in a bucolic valley with fantastic views of the Rocky Mountains.

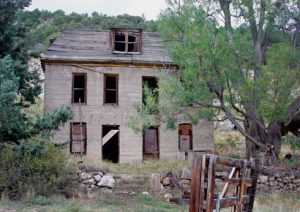

The few remaining buildings of Arbourville include a three story concrete parlor house, two log cabins, a shed, an outhouse and the remains of various animal pens and fences. Now a ghost town, this small hamlet was a vibrant stage coach stop along the Monarch Toll Road in the 19th Century, and was later the haunt of a self-proclaimed hermit who brought a great deal of flavor to Chaffee County.

Miners Arrive

Many of the early miners came to the valley that would become Arbourville by way of the Santa Fe trail, established in 1821. When a branch of the trail was laid in 1852 between La Junta and Canon City for trappers working the Arkansas River, Canon City began to grow, and by 1859, it had developed into a supply outpost for miners seeking gold in the mountains. A year later, Joseph Lamb began leading a pack train to the mines of the upper Arkansas River Valley. He followed Indian trails, establishing a route through Copper Gulch and Texas Creek. By 1874, stage coaches used this route and extended it past Salida, north to Centerville (present day Mesa Antero). In 1877, these stage coaches began running to Leadville to the old gold mining camps, quickly increasing their frequency with the discovery of silver in 1878. At that point, many of the miners who had been working in gold mines along the Front Range began to move into the Arkansas River Valley.

In 1879, Nicholas Creede discovered silver on Limestone Mountain (today’s Monarch Mountain) where he established the Monarch and Little Charm claims. Hugh and Sam Boone, who were partners in Creede’s venture, constructed the Monarch Pass Toll Road in 1880. The toll road began in Maysville and ended at Monarch pass. An existing road connected Maysville to the rest of the Arkansas Valley. The toll road serviced Maysville, Arbourville, Junction City (today’s Garfield), and Chaffee City (named after Colorado’s first senator, today called Monarch). By May 1881, stage coaches crossed Monarch Pass to the Tomichi mining district in Gunnison County.

Arbourville was established with the promise of mining in the area and its proximity to the nearly finished toll road. Its name derives from the fact that the town was situated in an arbor like setting of aspens and pines, or there is a possibility that a man with the surname of Aber or Arbour arrived with friends from Silver Cliff and were some of the first settlers. Throughout its history, the town has been called by several variations on the name, being called Aberville, Arbour Ville, Arboursville, Arbourville, and finally Arbor Villa.

When lots were first made available, it was said that over 100 parcels sold in the first day. By 1879, with the promise of mining on Monarch mountain, many cabins were under construction. Within six years, 150 people were living in the town. Occupants worked either as miners, working the mines three miles west in Junction City (Garfield), or raised livestock. In addition to private homes, the town boasted a post office, general store, boarding house, and hotel.

The Parlor House

The town’s largest building began as stage coach stop. By the mid 1880’s, it had become a “parlor house”. The parlor house, or brothel, is a large concrete building with a mansard roof that is visible from highway 50. During the 1880’s, Arbourville’s brothel was the only one in the area, was well run and well endowed. While nearby towns progressed in development, one reporter commented that Arbourville was content to let life revolve around the sociological norms of its parlor house.

The town’s largest building began as stage coach stop. By the mid 1880’s, it had become a “parlor house”. The parlor house, or brothel, is a large concrete building with a mansard roof that is visible from highway 50. During the 1880’s, Arbourville’s brothel was the only one in the area, was well run and well endowed. While nearby towns progressed in development, one reporter commented that Arbourville was content to let life revolve around the sociological norms of its parlor house.

The building was constructed sometime between 1879 and the early 1880’s. A large stately edifice, it rises to three stories and is capped by a mansard roof. The building’s construction is unique, being of concrete, composed of cement with glacial stone aggregate. Because steel reinforcing had only just been invented in the 1880’s in France, the building is not reinforced. Instead, the building was constructed using wooden forms. It appears that damage occurred during or directly after construction to the northwestern corner of the building. Repairs were made using handmade concrete masonry units scaled to fit.

It is extremely unusual that the facade is the untouched concrete, adorned only with the imprint of the form work. It appears to never have been clad with additional materials or painted. The strength of the concrete allowed for large windows on all facades of the building. The wooden mansard roof also sports windows within the roof line. The walls appear plumb and show little deterioration or bowing. Limestone, an important ingredient in concrete, was readily available in the nearby mountains. This may help explain why such an unusual construction material was used in this area. The remainder of the buildings were more typically constructed of wood.

The Denver & Rio Grande Railroad

In 1883, the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad began running trains up to the Madonna Mine just west of Garfield. The track generally followed the south fork of the Arkansas River. Near Arbourville, the rail completed several switchbacks and two trestles were constructed. One of the switchbacks formed a tight curve through the valley. The train then completed another switchback before crossing a trestle at Lost Creek, and bringing the track back to running along the toll road. The line was narrow gauge and ended at Monarch, 10,028 feet above sea level, rising 2,647 feet over its 20 mile length with maximum grades of 4.5 percent.

The train completed one round trip daily, taking two and one half hours to complete a one way from Monarch to Salida, today, a distance of roughly 20 miles. Initially used to transport ore from the mines, the train survived the 1893 silver and gold panic because a deposit of high quality limestone had been discovered at the Madonna Mine.

The limestone was quarried at Monarch and then transported to a limestone kiln in Pueblo. Transporting the trains up the valley and bringing the limestone back to Salida was an involved process. A locomotive, with a secondary engine at the back of the train, would push 56 empty train cars to Maysville from Salida. In Maysville, twenty eight empty cars would be left behind. The two engines would ascend past Arbourville to a set of switchbacks in Garfield. At the switchbacks the train would divide again with each engine taking fourteen cars to Monarch, where they would be filled with limestone. The train would rejoin at Garfield, bring the limestone down to Maysville, where it would exchange the filled cars with empty ones and begin the process again. When both sections of the train were filled, the train would return to Salida. In Salida, an automatic transfer machine, looking something like a large barrel, would pick up and turn the filled narrow gauge train cars upside down, emptying them into standard gauge rail cars that could then be taken to Pueblo.

From 1880 to 1905, 2-8-0 steam engines were used on the line. 2-8-2 Mikado steam engines replaced them until the 1950’s. In 1956, the narrow gauge track was replaced with standard gauge track. Diesel locomotives serviced the limestone quarry at Monarch until 1981, but finally, the track was removed in 1983.

William Henry Jackson Photographs Arbourville

At the height of Arbourville’s boom, the famous photographer William Henry Jackson photographed the town while commissioned by the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad. This image was recently included in the exhibition “Colorado: 1870-2000”.

William Henry Jackson began as a portrait photographer on the East Coast. Spurned by a woman, Jackson moved from the East coast to Omaha, where he continued portrait work and also began photographing frontier life, landscapes and American Indians. He and a friend soon hatched the idea of photographing the west by riding the newly completed transcontinental railroad. They would purchase a one way ticket to the next town, provide photographic services for as many portrait pictures as possible, develop and deliver the portraits, collect the money and buy one way tickets to the next town.

At the same time, Ferdinand Hayden, the director of the US Geologic and Geographical Survey of the Territories, was running the federally funded Hayden Survey of the West, mapping, assessing resources, and studying plant and animal life. At the end of each summer, results of the survey were reported to Congress. Several other expeditions by the likes of John Wesley Powell and Clarence King were also vying for funds from the Federal Government, and Hayden quickly realized that the expedition that provided the most compelling images of the West would be most favored for funding. Hayden heard about Jackson?s work, and subsequently employed him from 1870 to 1880 as a photographer for the expedition.

Working with Sanford Gifford and Thomas Moran, Jackson quickly developed a clear style to his work. The first published photographs of Yellowstone Park were attributed to Jackson. The photographs arrived one week before Congress voted on Yellowstone, and were said to be instrumental in it becoming the first National Park. In 1873, the Hayden Survey focused on Colorado, and Jackson’s panoramic photographs helped to fuel tourism to the area.

In 1881, Jackson received a commission from the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad to photograph landscapes along the rail lines. Commissions were also given to Thomas Moran and Ernest Ingersoll. Ingersoll’s writings, Moran’s paintings and Jackson’s photographs were used by the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad to promote “The Scenic Line of America.” In addition, the works of these three were published in Harpers and privately published “booster” books promoting tourism.

Sometime in the 1880’s, while working for the Denver & Rio Grande, Jackson photographed the town of Arbourville. His work with the Railroad continued until the 1893 silver crisis, when the U.S. Government stopped using silver and gold as the money standard. Facing bankruptcy, Jackson accepted a commission from Cornelius Vanderbilt, George Westinghouse, Andrew Carnegie and other prominent Mercantilists to photograph railways throughout the world for a proposed Museum of the World’s Railways. Money for the venture ran out in 1896.

Facing bankruptcy again, Jackson joined the Detroit Photographic Company. The company had developed a way to make realistic color prints from black and white photographic negatives. Jackson contributed his negatives to the companies holdings, and maintained the company’s stock photography archive of over seven million images, controlling popular taste through the issuing of everything from postcards to giant panoramas.

After Jackson’s death, the Detroit Photographic Company (later Detroit Publishing Company) gave it’s holdings to the Edison Institute of Dearborn, which then donated the photographs to the Colorado Historical Society. In turn, the Colorado Historical Society gave all photographs of places east of the Mississippi to the Library of Congress. Photographs of the West are still held by the Colorado Historical Society.

John Fielder, a renowned contemporary photographer, recently developed the “Colorado: 1870-2000” exhibition, choosing 300 photos from over 22,000 photos in Jackson’s archives. Fielder then re-photographed the originals, some 130 years later, in his own style, documenting how much change, or how little change, had occurred during the ensuing years. A photo of Arbourville was one of the 300 chosen for the exhibition, and is held by the Denver Library. The monograph from the exhibition is published under the same title “Colorado:1870-2000”, and, in addition to the photographs, has several well composed essays regarding Jackson’s life and the history of Colorado. The book is often used as a textbook in Colorado schools.

The Hydroelectric Plant

A series of hydroelectric power plants were constructed along the South Fork of the Arkansas River and its tributaries to supply electricity to power machinery and ventilation equipment in the nearby mines. Between 1905 and 1906, hydroelectric plant #1 was constructed to the east of Arbourville by Salida Light, Power and Utility Company.

The brick building sports Victorian detailing, and is easily visible from Highway 50. Water is supplied by a thirty inch diameter steel pipe that runs through the valley. The pipe delivers water to a turbine located in the building. The water is released from the turbine into the reservoir, where it is recaptured to fill the continuation of the pipe to the next hydroelectric plant downstream. The original GE generators and Hub Turbines were replaced in 1929 by a new 750 kw GE generator and a S. Morgan Smith Turbine. The other hydroelectric plants are located along Fooses Creek and east of Maysville. Today, the reservoir is a popular place to fish, being stocked with rainbow trout by the Colorado Department of Fish and Game. The electricity is now used by the city of Salida.

Frank E. Gimlett, The Renowned “Hermit of Arbor Villa”

Born on July 22, 1875, Frank E. Gimlett would go on to be the most well known resident of Arbourville. In 1879, Frank Gimlett arrived in Junction City with his parents, Mr. and Mrs. Edward Gimlett. He lived in Chaffee County his entire life: mining, building and selling homes and eventually going into the wholesale coal and feed business in Salida. An accomplished pianist, he ran the Salida Opera house for many years. In 1897, he married, fathering two children.

Gimlett was most well known as the Hermit of Arbor Villa, a self proclaimed title. Under this moniker, he wrote nine short booklets under the title of Over Trails of Yesterday, Stories of Colorful Characters that Lived, Labored, Loved, Fought, and Died in the Gold and Silver West.

He sold these booklets primarily to tourists, with prices ranging from thirty five to fifty cents. The booklets include loosely retold histories of the boom towns of the Arkansas River Valley, essays on reinstating the silver and gold standard (including several letters to Congress), diatribes on the loss of feminine attributes in the new modern woman and in depth writings on the life of a prospector. In his books, he commented that he was “alone in defending gold and silver money the only hope of any Nation, alone in a crusade to replace saintly women on theat pedestal of modesty, mystery, constancy and alluriveness from which she has tumbled.” (Book 2, page 52)

The Mountain Mail, in its obituary, referred to him as one of Salida’s best known and best loved citizens, going on to state that he “was the friend of movie stars and statesmen over the nation.” According to the Mountain Mail, after retirement, Gimlett was the second person to purchase the entire town site of Arbourville, which he referred to as Arbor Villa. He grew out his beard and began calling himself the “Hermit of Arbor Villa.” He traveled extensively, delivered speeches over the radio and wrote to congress several times in an attempt to reinstate the gold and silver monetary standard.

The following are some examples of his writings. Much of it was quite humorous, especially when dealing with the everyday trials and tribulations of being a prospector:

“And I leave my cabin amidst the tall silver spruce trees, and as ever my enemy and companion the Mountain Rat eyes me with hate exemplified in every move, feeling perhaps that I may not return, and he is to be cheated of a satisfaction of feasting on my carcass. The hate is mutual and on some final day it will be war to the finish between we two. The caw! caw! Of the camp robber (robin), whether meaning good bye, good riddance or the reverse I cannot say, but I do know my one tried and true friend (helpful in many emergency) Minnie the porcupine looks on my departure with regret.” (Book 2, page 5)

Starting in 1909, issues of water rights became important to both Colorado and the Hermit. People who had settled along the lower Arkansas River were clamoring for greater supply of water, and as a result, limitations on water usage in the Arkansas River valley were enforced. The Hermit was convinced that the water limitations would turn the verdant upper Arkansas River valley into a desert. In book one of “Over Trails of Yesterday”, he threatens to remove the water from the lower river valley:

“… now comes the Hermit defender of the people, who inadvertently holds within his hand, the destiny of the headwaters of the Arkansas and Colorado rivers. And now with next year’s water safely stored away in ice and snow banks high up atop the Great Divide, he demands his and all the people’s rights on dire threats, that if not complied with, he will either divert the the Arkansas river to the Pacific slope thru a tunnel already provided by some soldier of chance in his search for buried treasure, or will convey through another high line, high altitude canal to whomever or wherever he may choose, and will also include in the transaction at a nominal price, all the rain that falls on his mining property during the months of July, August, and September. So decrees the Hermit.” (Book 1 page 28)

The Hermit went on to send a bill to Congress, for $50,000, for protecting the snow and ice along the Continental Divide from being stolen. He commented that not one shovel full of snow had been removed during his watch. This request for payment seems to be a continuation of his refusal to support water rights for those living on the Lower Arkansas River.

Gimlett also felt deeply that it was his duty to protect the history of the boom towns along the Arkansas River Valley. He was deeply disturbed when the new road grade for Highway 50 was constructed over several pioneer cemeteries. In particular, he comments upon the cemetery at Junction City (now Garfield):

“After several months of watching and waiting with numerous pleas to the highway engineers to spare this hallowed spot, they like a thief in the night, steal upon the lost and almost forgotten cemetery of Junction city, desecrate and disseminate along the highway grade the bones of old pioneers….ruthless in their purpose, vicious in execution and seemingly immune to the spiritual rights of the dead, they come forth in the dead of night with that insatiable ogre, the poser shovel, and with these jaws of Moloch, and with fiendish glee, did dig up and crush the bones and caskets, dump in the trucks and haul away the remains to build up the highway grade. This modern method in great contrast to the railroad engineers and graders who, when building through this same cemetery with caution and great reverence, removed the bodies one by one to individual graves elsewhere.” (Book 6 page 42-43)

The Hermit labeled this portion of the highway “The Ghost Highway of the Rockies”, stating:

“Mingling souls and bones of deadly enemies and foes, paragons of virtue and disciples of vice, saints and sinners, they will not lie at rest, and their rebellious spirits will forever haunt this stretch of highway in search of missing parts and seeking a spot where they may abide in peace and alone.” (Book 6 page 45)

He also commented upon the Arbourville Cemetery with:

“Progress at what a price to the desecrated and disseminated pioneer. These modern vandals and ghouls (harsh words) of to-day do not give a passing thought to the traditional landmarks or respect old soldiers of chance else they would not survey and build highway 50 thorough the Old Arbourville Cemetery.” (Book 2 page 53)

Later, Gimlett commented that the graves in Arbourville were undisturbed by the highway grade, being simply covered with fifty feet of road base.

In addition to roaming the continental divide, writing and running several businesses, Gimlett also found time to mine. He worked Mount Aetna, adjacent to Mount Taylor. As perhaps one of his zaniest ideas, he proposed to rename this peak:

“From the beginning of Ginger Rogers career I always admired her ability and genius as an actress and dancer, mailed her a verse now and then to this effect, and while sitting on the old mine dump or gazing through the cabin window after the day’s work was done, I could envisage her in comparison with the beautiful Mountain Peak, tall symmetrical and streamlined, a golden crown upon her head, a chilly atmosphere encompassing her at times…. But more than all as I watched the glistening flakes of snow, swirl and sweep about the crest of the Peak, revealing the outlines of its delicate lined symmetrical form through the mist, I envisaged Ginger in her dances gowned in flimsy, lacy diaphanous skirt, whirling and gloating about displaying at times the outlines, of a modified, curvaceous figure of perfection.

Thus I named the Peak GINGER, and going so far as to dig a bag of gold from its heart to exchange for the heart of Ginger herself…. There was some opposition to renaming the Peak, both members of the interior department and the Governor of Colorado himself, but knowing mines covered the peak and with dire threats of digging it down unless allowed the privilege of renaming to suit myself, thus leaving Colorado with only 49 peaks over 14 thousand feet high, and one less for the United States, opposition died down and now by usage and tacit consent it will be know as GINGER PEAK.” (Book 6 page53-55)

Evidently, Gimlett did indeed contact the U.S. Government regarding renaming Mount Aetna “Ginger”, even writing a letter to the President. Supposedly, Franklin Roosevelt replied back, saying he also thought it was a good idea to rename the peak, but that he could not get support for it in the government, given the expense and time it would take to have the cartographers change the name. Evidently, residents of the Arkansas River Valley, at the Hermit’s behest, adopted calling the peak “Ginger”.

On February 1st, 1952, Frank Gimlett died, following the pioneers that preceeded him “Over the Great Divide.” Today, as one looks to the west from Arbourville, one can still see in the setting sun, the “Golden clouds with Silver linings” that he often referred to in his books as hallmarks of the “Gold and Silver West.”

Highway 50

Arbourville is located adjacent to Highway 50. This highway is one of the longest in the country, running just over 3,000 miles from Ocean City, Maryland on the Atlantic Ocean to West Sacramento, California. It goes through Washington DC, St. Louis, Kansas City, Lake Tahoe and at one point connected through to San Francisco. When it was constructed, it was conceived as one of the few transcontinental highways in the country.

US 50 leaves I-70 upon entering the western edge of Colorado and heads southeast through Grand Junction and into the southern part of Colorado. Once there, the road climbs to its highest elevation of 11,312 feet over the Rocky Mountains and over Monarch Pass where it crosses the Continental Divide. As it descends it passes by Monarch Spur RV Park, continues on through Poncha Springs and Salida then heads down the canyon beside the Arkansas River. US 50 passes near the Royal Gorge through Cañon City and follows the Arkansas River through Pueblo where it intersects I25 then on to La Junta, Lamar and into Kansas.